Ever since it was announced, I have been eagerly awaiting this exhibition. In fact, you may have even read about it months ago in my list of shows to look out for this year – a testimony to my long wait. In October, I finally experienced Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, and it did not fail to impress.

I already think that Lucian Freud is one of the best painters of the 20th century. If you aren’t also convinced, I am sure that this panoramic exhibition of his impressive career will nudge you to my side. Spanning a lifetime of works and featuring over sixty paintings, this is the first major Freud exhibition in ten years. His dedication to portraiture is inherently clear in every piece; he never over-embellishes or flatters his sitters but presents what is right before him. More to the point, Freud’s portraits are unpretentious. He appears to depict fellow artist David Hockney with the same level of scrutiny and impasto as the late Queen. (Although the Queen conducted her sitting in a far more tidy and respectable space, whereas Hockney was seated in Freud’s rickety paint-smeared studio for days.)

Interior With Plant, Reflection Listening, (1968)

The grandson of Sigmund Freud, Lucian was born in Berlin in 1922. When Hitler became chancellor in 1933, he and his parents fled to England; Freud was just 11 years old. From a young age, he exhibited a talent for drawing but had an equally rebellious spirit when it came to school rules. After an unsuccessful stint at The Central School of Art in London, he completed art school at Cedric Morris' East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in Dedham.

His earlier canvases tend to be small in scale and are linear and detailed. In fact, looking at Girl with a Kitten (1947), which depicts his first wife Kitty Garman, one could draw parallels to Dutch and Flemish Renaissance paintings. Perhaps it’s the pallor of the young woman’s skin contrasted with the bleak interior and dark clothing – or her concerned expression and what appears to be a symbolic rose in her hand – that helps draw that conclusion. Also present is Freud’s characteristic ability to inject a glimpse of a narrative yet leave it tauntingly ambiguous. Here, Kitty is pictured looking off into the distance – is she disappointed in her relationship with the artist, or weary of her partner’s infidelities?

Left: Girl With A Kitten (1947) Right: Still-life with Green Lemon (1947)

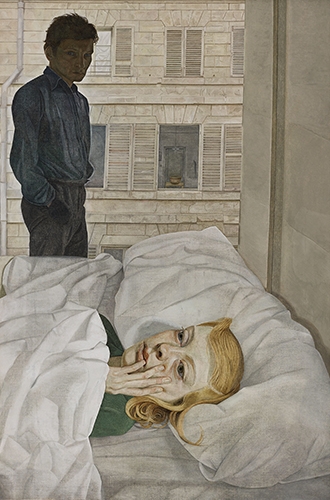

Freud’s tumultuous relationships peppered his life, and their traces can be found in many of the paintings in this exhibition. In late 1952, he eloped to Paris with Guinness heiress and writer, Lady Caroline Blackwood. They consequently married in 1953 but, like his first marriage, it resulted in divorce in 1959. Hotel Bedroom (1954) appears to be inspired by ths, depicting a moment of anxiety that remains, for the larger part, obscure. Lying in bed with her hand resting on her cheek, Lady Caroline appears to be deep in thought, even troubled. Her eyelids could be puffy from sleep or from tears. Behind the bed, Lucian lurks in the darkness, an expression of concern or perhaps regret on his barely lit face. An open window from another flat across the road is visible through their own, hinting at the quotidienne dramas all around.

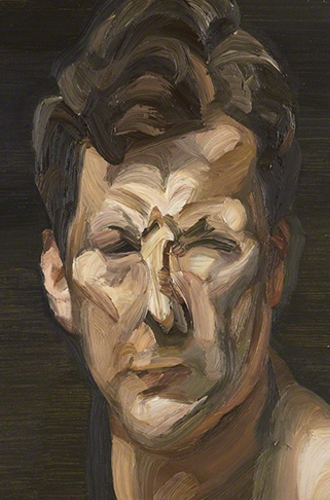

Left: Hotel Bedroom (1954) Right: Lucian Freud (1963)

Stroll through the next galleries and fast-forward a few decades, and you see Freud’s painterly style shift to the heavy impasto of his late career. If you decide to meander through the rest of the National Gallery and through the permanent collection, you’ll recognise Titian’s influence in Freud’s imposing and fleshy nudes. Titian’s two masterpieces Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto, which Freud campaigned to buy for the nation, certainly come to mind when you stand in front of the latter’s And the Bridegroom (1993).

Freud’s connection to the National Gallery is certainly deep-rooted and highlighted in his own statement, ‘I go to the National Gallery rather like going to the doctor for help.’ When elaborating on this remark, Freud explained that whenever he needed inspiration or help painting a particular subject, he would look within the motifs of the paintings in the collection. In fact, late in his career, the artist benefited from unlimited entry to the gallery at any time of the day or night – an honour rarely granted even to affiliated artists.

By the time he died aged 88 in 2011, Freud had been a powerful, incisive, and sometimes controversial presence on the international landscape for more than six decades. This retrospective celebrates his position within the centuries-old narrative of portrait painting and highlights his place within and contribution to that history. It’s an absolute must-see this autumn!

To learn more about Quintessentially's art programme or Bojana Popovic, please contact your lifestyle manager.