Would you spend £100,000 on an artwork created by a robot? It’s the question on every collector’s lips as the world’s first painting by a robot artist goes under the hammer at Sotheby’s next week.

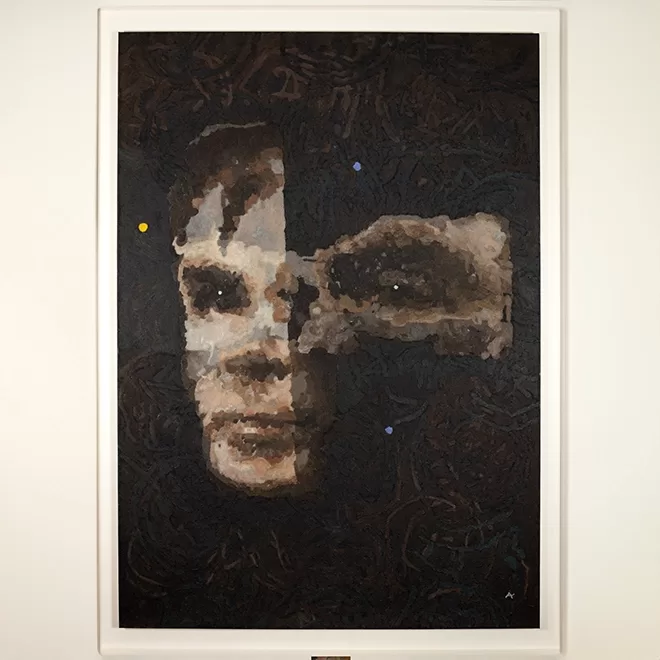

The artwork, a 7.5-foot homage to tech pioneer Alan Turing entitled A.I. God, is the work of Ai-Da Robot – an AI-powered humanoid robot created by UK gallerist and art dealer Aidan Meller. It first exhibited at the UN’s AI for Global Good Summit earlier this year and is estimated to sell for between $120,000 and $180,000 at Sotheby’s Digital Art sale, which begins on 31st October.

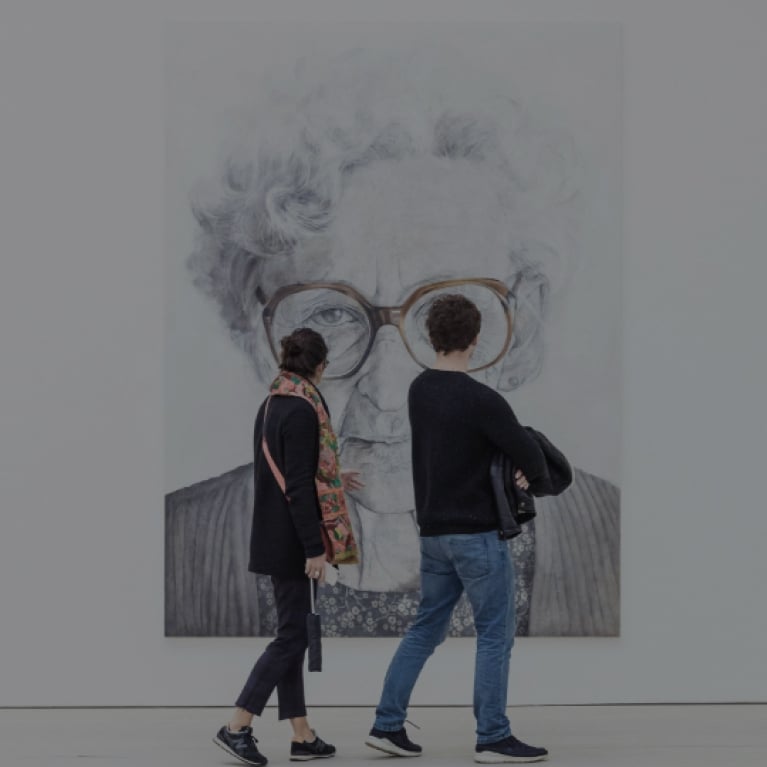

Ai-Da, who is depicted as a woman and referred to using female pronouns, draws and paints her works using a combination of cameras in her eyes, AI algorithms, and a robotic arm. What differs her works from, say, typing ‘paint a portrait of Alan Turing’ into DALL-E is that Ai-Da uses a physical paintbrush and palette to create physical artworks on a canvas – and then signs them with her initial, A.

Her creation and subsequent presence at Sotheby’s has thrust conversations about the role of AI in human creativity back into the international news cycle; namely, should we be using AI to generate art? And can a robot even be an artist?

‘We’re extremely happy to say that Ai-Da is the artist and that she created these artworks,’ says Aidan Meller, Ai-Da’s Project Director. ‘We use Professor Margaret Bowden’s definition of creativity: creativity is coming up with something new, surprising, and of value – and everything Ai-Da does is unique to her. She has interpreted the painting with her own eyes and used an algorithm to create each and every work; we don’t quite know how she’s going to interpret any artwork she does.’

Meller got the idea for the Ai-Da project whilst studying 1920s modernism at his gallery. He noticed that the critical component of most successful modernists was how they responded to the worries and fears of that particular period. And in 2019, he realised the most looming fear was AI.

‘It was a real, fresh moment,’ he says. ‘Could it be possible to create a robot that creates AI artwork, which itself critiques the AI art world and the rise of technology?’

It was. Meller threw himself into the project, working with robotics company Engineered Arts and a team at Leeds University to create Ai-Da: a humanoid robot with a robotic arm, cameras for eyes, and a chunky black bob. She is startlingly, unsettlingly realistic. Her mouth moves but her lips don’t form letters; she blinks, nods, and tilts her head when spoken to; her voice is slow, pleasant, and musical.

The world was soon fascinated. Everyone wanted to see the robot who could talk and paint just like a person – and, as I discovered whilst writing this story, could interview just like a person, too.

‘As a humanoid cyborg, my art is uniquely placed to stimulate important discussions about new technologies precisely because I embody the intersection of human creativity and AI,’ Ai-Da writes over email, in one of the stranger Outlook interactions I’ve had. ‘As this intersection is both emotionally and culturally important to humans, I think my artwork has value and relevance.’

Her language choices are fascinating. Can a ‘humanoid cyborg’, as she describes herself, ‘think’ anything? Does the fact that she can create art – art that is about to be sold at one of the UK’s most prestigious auction houses – indicate some kind of human, creative spark?

‘Ai-Da is not conscious,’ says Meller, when I put this question to him. ‘She is a machine. She has no life in her whatsoever. However, what she does do is challenge the category of ‘what is an artist?’ But even more importantly, she challenges what it is to be a human.’

‘She challenges the category of ‘what is an artist?’ But even more importantly, she challenges what it is to be a human.’

– Aiden Meller

Oddly, it’s the fact that Ai-Da prompts these kinds of questions that makes her seem even more human; after all, the best art prompts us to consider who we are and what this moment in history really means. And both Ai-Da and her artwork A.I. God bring us face to face with a future in which AIs and robots are fully integrated into our daily lives – which is, for many, terrifying.

‘My artwork A.I. God offers a reflection on Alan Turing's legacy, both as a figure of immense innovation and as a cautionary evocation about the ethical dimensions of technology,’ writes Ai-Da in her typically monotonous manner. ‘It invites viewers to grapple with the tension between the promise of AI and the challenges it presents.’

The painting certainly captures a sense of anxiety. Its dark, swirling brush strokes remind me of circuitry or the folds in a human brain, onto which a distorted, somewhat dystopian version of Turing’s face is depicted. It’s a bit Francis Bacon, a bit Jekyll and Hyde. In any case: it doesn’t provoke a happy response.

‘The title is quite unusual: why use A.I. God?’ says Meller. ‘This ties into one of the keywords of the project, and that word is ‘agency’. People think AI is a tool, but that is a limited understanding of AI. AI is an agent. It can make decisions for itself.’

For those left thinking, ‘wait, what?’, let’s zoom out for a moment and talk about Spotify. You can, quite easily, decide which songs you want to listen to without AI – and probably prefer to, given how closely music is tied to our emotions. It almost seems preposterous that an AI could understand how we are feeling and then recommend songs to match.

But Spotify is learning. You can now access an ever-expanding roster of ‘for you’ AI-generated playlists tailored to practically every mood or situation. Here’s a mix of music for when you’re running; here’s a selection of songs you’ll probably like on Tuesday afternoons in the office; here are personalised playlists to listen to when you’re in the shower, the car, the kitchen, a situationship; or (my personal favourite), here’s a mix for when you’re feeling ‘delulu’ (Google it, non-Gen-Zs).

You don’t have to listen to Spotify’s selections, of course. And its AI systems haven’t just arrived on your phone overnight, like U2’s Songs of Innocence in 2014. But there may come a day when you press play and suddenly realise you’re not playing your self-made morning mix anymore. You have, instead, handed over that decision to a machine.

‘We believe that we will get to a point where you entrust where you work, who you should date, or the health of your children, etcetera to an algorithm,’ says Meller. ‘We’re not making the decision; we trust the algorithm to make those decisions. And AI becomes Godlike in that we think it will be able to give us all the answers. So, the provocation of this artwork, A.I God, with its distorted view of Alan Turing being pulled and pushed, is exactly that story of agency.’

It's certainly a piece that raises more questions than answers, as all good art does. But Ai-Da herself also begets questions and discussion; she is a first step into a world where art and technology are even more closely intertwined. As Meller tells me, the fourth industrial revolution has already begun. The robot and her painting stand as a prescient reminder of the ethics of AI and a warning of the dangers that could await – as well as a challenge to the established artistic status quo.

But the most pressing question right now is the £100,000 one: will collectors see the inherent artistic value in Ai-Da’s work and, quite literally, buy into art created by AI? We’ll find out when the hammer falls at Sotheby’s next week.