No holding back – this is the best exhibition I have seen in a long time. Perhaps I am biased because I love portraiture and this show features several of my favourite contemporary painters. Still, even if you aren't there to see the excellent selection of Hurvin Anderson paintings and Njideka Akunyili Crosby's masterpiece, there is an eclectic mix of sculptures, collages, and canvases by a range of top artists working today.

The exhibition, curated by writer and former director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London Ekow Eshun showcases 22 contemporary artists from the African diaspora who bring to light the richness and complexity of Black life. As well as examining the presence of the Black figure in Western art history, what is more significantly brought to the fore is its striking absence.

At the entrance of the exhibition, Thomas J Price's colossal bronze full-sized female figure, As Sounds Turn to Noise, immediately creates a dialogue between old and new: using the modern technology of 3D scanning, he casts a figure that could be someone we'd bump into on the streets of London or Los Angeles. The historically loaded medium is given a contemporary lease of life, eternalising a relaxed Black woman in gym gear, frozen in time while briefly pausing after her workout. In this way, Price gives visibility to bodies often marginalised or excluded from art history and classical sculpture.

A few rooms later, Wangechi Mutu uses the same medium to form a self-portrait, This Second Dreamer, referencing Constantin Brancusi's Sleeping Muse (1910), which provided the initial inspiration. Likewise placed horizontally, eyes closed, it appears with a crown of braided bronze hair, shining with a high-gloss golden finish. This is an Afrofuturist reimagining of an iconic work of 20th-century modernism.

American artist Kerry James Marshall creates a captivating double portrait of a female painter, playing with the composition to present the artist with paintbrush and palette in hand in front of her canvas –wherein the outline of the same form is already defined. Upon closer inspection, she uses a 'paint by numbers' guide, perhaps to signal the omission of black figures in Western Art history as she leaves the skin unfinished.

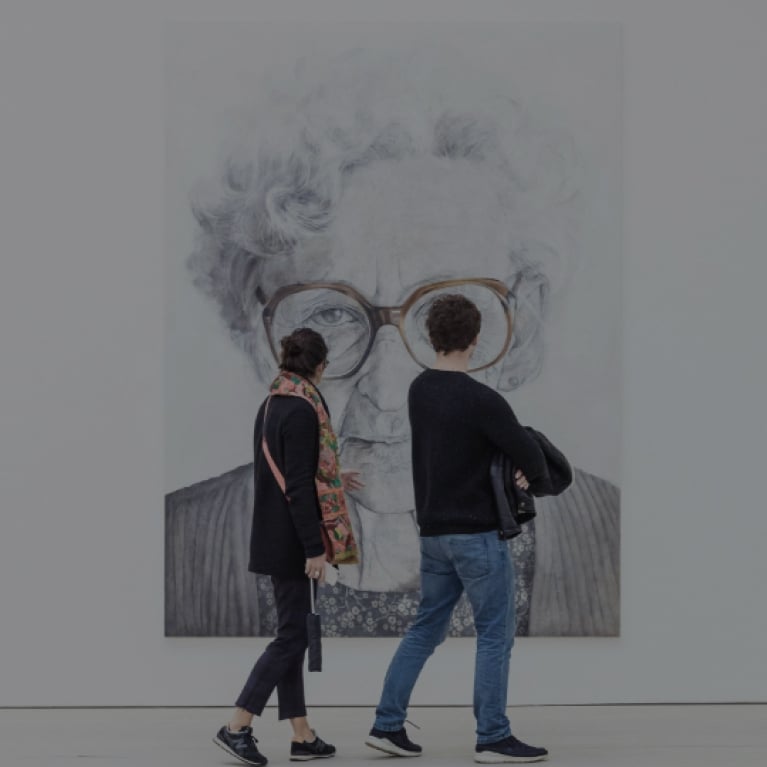

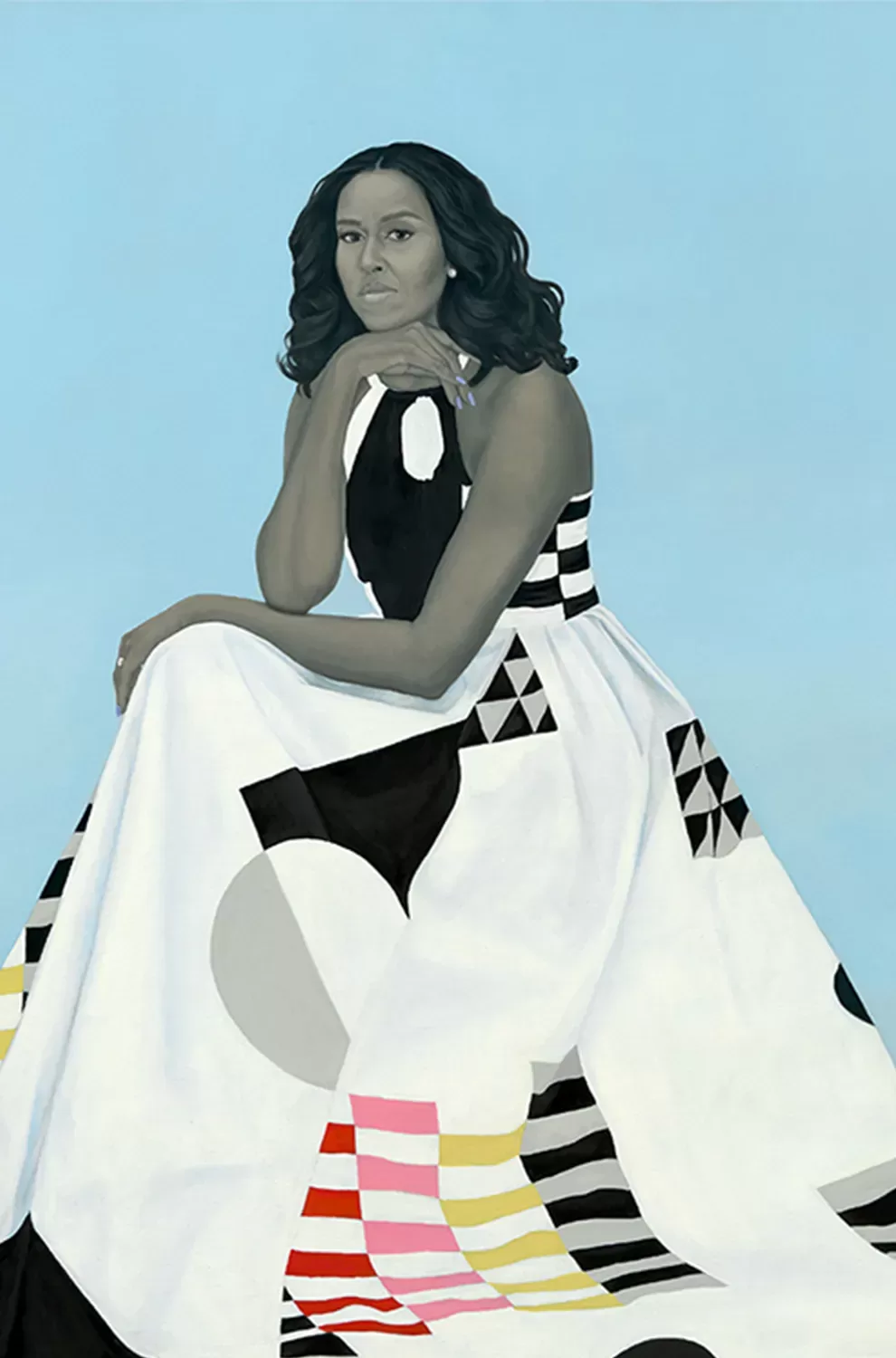

The composite portraits of Nathaniel Mary Quinn present his male sitters as vulnerable and sensitive, exposing the damaging effects of exaggerated Black masculinity, which, quite literally here, breaks the person apart. Amy Sherald, in a different way, draws attention to skin colour by eradicating it altogether – rendering her figures' skin in grayscale, sharply juxtaposing the vibrant tones of the background scenes.

Sherald was commissioned to paint the official portrait of once-First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama. Describing her process, Sherald said, 'my work began as an exploration to exclude the idea of colour as race from my paintings. By removing colour but still portraying racialised bodies as subjects to be viewed through portraiture, I challenge the nomenclature of both terms and their usefulness as identifiable markers.'

Tojin Ojih Odutola's portraits feature a fictional aristocratic Nigerian family, but the paintings are not simply an inversion of historical imagery where white sitters are replaced by Black ones. Instead, they offer a deeper counter-narrative that imagines white presence as absent and conjures Black life as both ordinary and extraordinary. They are an ode to the Black presence and the richness of Black being. Furthermore, in these compositions, the artist draws on the power of storytelling, saying, 'the best gift I received from growing up in a Nigerian house, and in the community at large, was the beauty, magic, and energising spirit of storytelling.'

Many of the works included in this exhibition strongly resonate with the art of storytelling. Kimathi Donkor's large-scale pictures reimagine a historical female commander, Queen Nanny – leader of the Maroon guerrillas who fought the British in Jamaica during the 1700s. Compositionally, it is based on Joshua Reynold's portrait of Jane Fleming, later Countess of Harrington (1778), who, as the artist described, 'was an aristocrat whose family was involved with enslaving people in the plantations in Jamaica, brutal exploiters. I made her portrait into the figure of her arch-enemy, Queen Nanny of the Maroons.'

He continues. 'Jane Fleming's family was involved in the oppression of Jamaica, and the painter Reynolds, one of the founders of the Royal Academy of the Arts in England, took her money to finance his studio. I have inhabited Fleming's body with the body of a contemporary young British Nigerian woman who poses as a model for Nanny. It is something which you can do through art. Art can do something a bit magical with history; the two things aren't separate. All artists work with history anyway and with the history of art. Whenever artists make work, they enter the stream of our history.'

On display until 19 May 2024, this exhibition is definitely one not to miss this year.

Want to be invited to private tours, previews, and talks at the most esteemed art and cultural events around the world? To make it happen, we work alongside the most prestigious artists, galleries, museums, auction houses, and art fairs globally. Find out more about a Quintessentially membership here.