I’ve been speaking to Dr Rebecca Struthers for 20 minutes and we’ve already discussed the impact of the Industrial Revolution on horology, art versus AI, and how we’ll measure time in deep space. Okay, and we’ve also spoken about her favourite watch (the solid emerald watch from the 1912 Cheapside Hoard – although a Casio is her favourite for everyday use).

If that didn’t give it away: Rebecca Struthers knows a lot about watches. She’s not just one of the UK’s few remaining artisanal watchmakers (a craft that has been listed as ‘endangered’ by the Heritage Craft Association), but she’s also the only one to have a PhD in horology – she is genuinely a ‘watch doctor’. Her first book, Hands of Time: a Watchmaker’s History of Time, has been widely praised within the watchmaking world and beyond, and she’s in the beginning stages of her next book, which will use watches and clocks to teach children about science and history.

Images by Mike Smith (L) and Andy Pilsbury (R)

‘Watchmaking is both design and science; engineering and art,’ she says. ‘It’s quite sentimental, which is an interesting overlap as watches are precise, scientific instruments that are also crafted by human hands.’

Struthers is an artisanal watchmaker, meaning she does every part of the watchmaking process by hand, using tools and techniques that have been passed down for generations. Her design ethos is ‘we look backwards to look forwards’, often taking inspiration from restored historic timepieces (although these days, she only offers restoration to her VIP clients as demand for bespoke watches has soared since the release of Hands of Time).

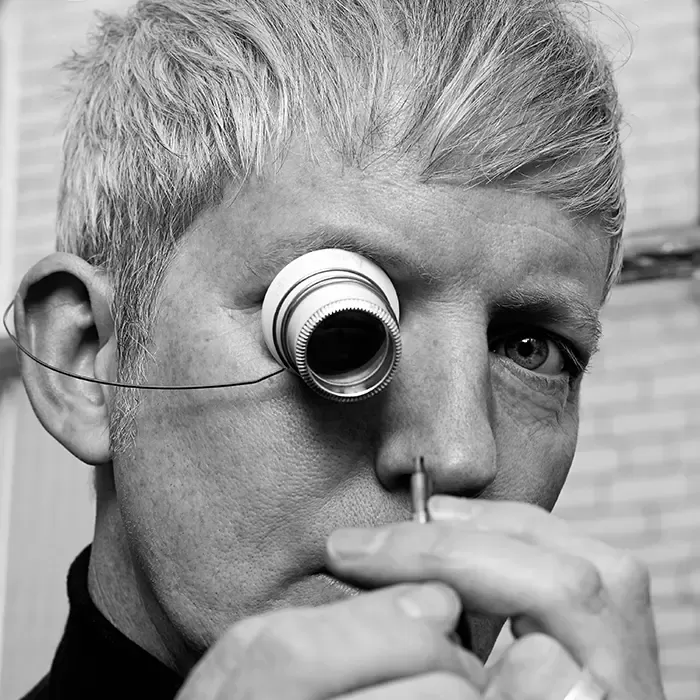

Image by Andy Pilsbury

‘Watchmaking is both design and science; engineering and art’

– Rebecca Struthers

‘The oldest tools we have here are mid-19th century up until the 1960s and ‘70s,’ she explains. ‘Some of the turning and hand-finishing methods have been done for centuries, and a lot of the finishing techniques we use are also centuries old.’

It takes between 12 months and six years to create a single watch – and demand is only growing. The luxury watch industry’s biggest year to date was 2022, with researchers anticipating a further $20 billion growth in the next five years. The reason for this is an increasing perception that owning a luxury watch is a symbol of financial success and social status.

‘500 years ago, watches used to be incredibly expensive luxuries that would take years to make and only a few could afford,’ says Struthers. ‘It wasn’t just about the value of the object; it was about it being the latest in science and technology, and us being able to display our knowledge about the world through the technology we owned.’

You might think that today’s equivalent of owning or experiencing the latest in science and technology would be something like space travel or a private jet. But over the last couple of years, owning a top-of-the-range watch has once again become a common symbol of wealth – which is welcome news to makers like Struthers.

Image by Andy Pilsbury

‘Nowadays, [luxury] watches don’t have to be practical – if we want to spend years crafting something out of the finest materials, we can,’ she says. ‘Designers and makers are pushing the boundaries of technology and exploring what it means to be a watchmaker, and that creates a really exciting opportunity for collectors.’

‘Designers and makers are pushing the boundaries of technology and exploring what it means to be a watchmaker’

– Rebecca Struthers

Image by Asia Werbel

One of Struthers’ interests – which she dives into in detail in her book – is what watches can tell us about the moment they were made and, specifically, what they can tell us about our relationship to time. I ask her what conclusions horologists would draw from watches made today and, in particular, the increased popularity of smartwatches. Her answer is expectedly philosophical.

‘The evidence we have implies that our earliest understanding of time started with things like lunar cycles,’ she says. ‘And smartwatches measure a lot of things that we started out measuring 40,000 years ago; it’s like everything still comes back to that despite the advances we have made. Several of the timekeepers currently on Mars Rovers even use sundials.’

The advent of commercial space travel is, without doubt, going to cause a seismic shift in how we measure time and – even more mind-blowingly – may mean we need to reconsider our concept of time altogether.

‘The big future question for me right now is what our future time is going to look like,’ she says. ‘When people are living on the moon or travelling into deep space, then our understanding of a circadian rhythm around 24 hours a day is no longer going to have any meaning. So, how are we going to adjust ourselves to time in the universe when Earth time will no longer have any meaning?’

It’s certainly a headscratcher. But it also begs the question of what the watches of the future will look like – and if 22nd-century watchmakers like Struthers will still use 19th-century tools to make them. Only time will tell.

Want to stay up to date with the latest in luxury? As the world’s leading luxury concierge service, we spend time securing you access to the best of the best across the world, so you can spend more time doing the things you love. Discover more about membership here.