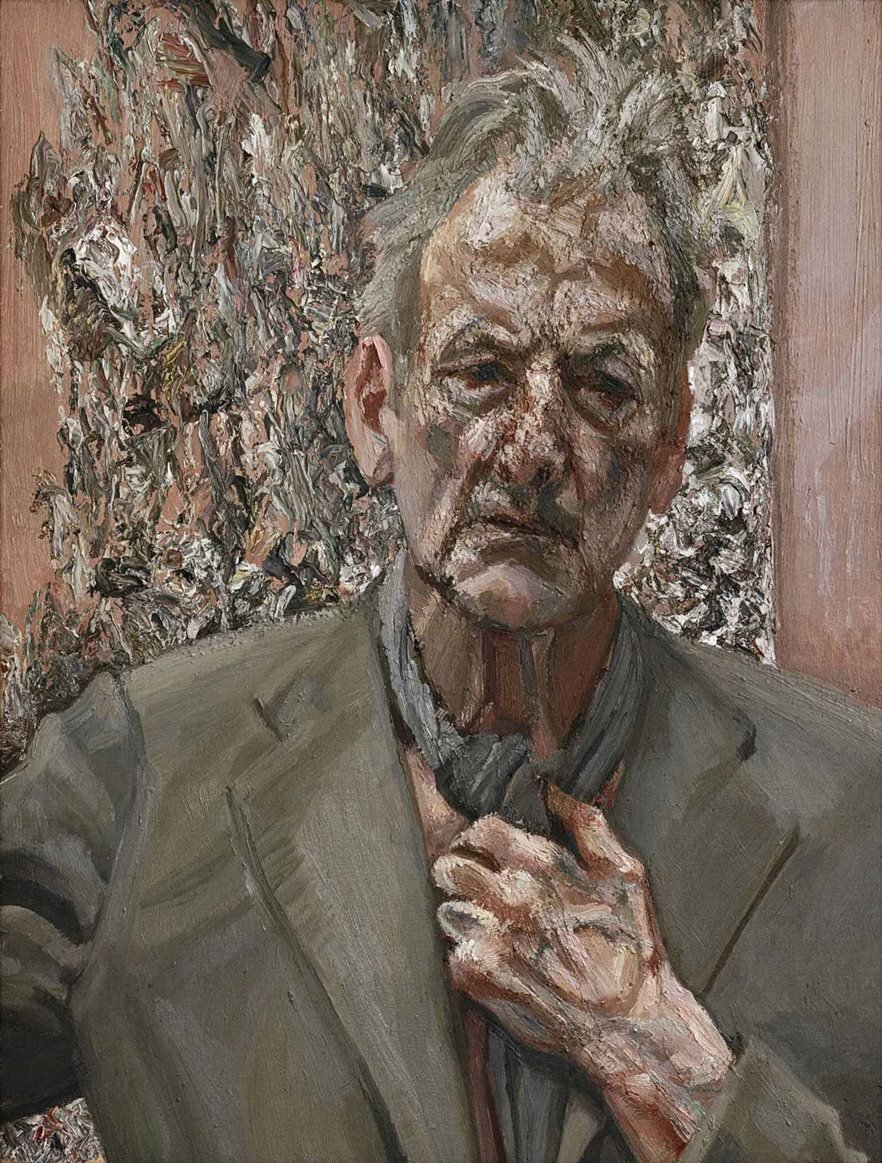

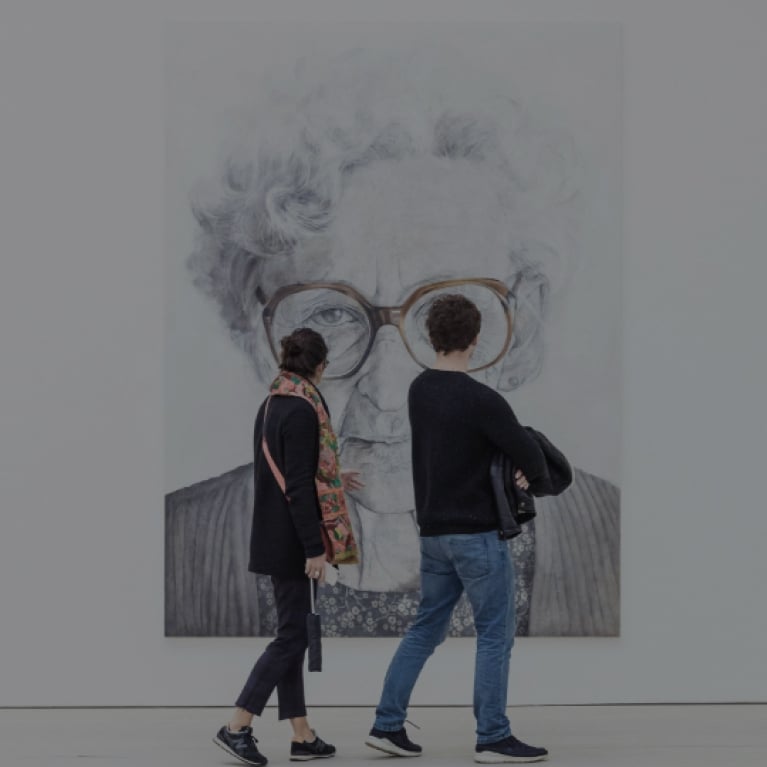

‘My work is purely autobiographical,’ said Lucian Freud in a famous statement: ‘It is about myself and my surroundings.’ In reflection of the Royal Academy’s recently opened exhibit of over 50 self-portraits by Freud—the first exhibition of its kind—Quintessentially chats with curator Jasper Sharp about the celebrated British painter and the unique show.

Keven Amfo: You have curated a comprehensive career-spanning survey of Freud’s work before (at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien in Vienna, 2013), but this show is much more specific. How did the processes of idealisation and curation differ between the two?

Jasper Sharp: The two shows are very different, but I felt great responsibility with both. Vienna was intended to be more of an overview of his entire career. It was his first-ever exhibition in Vienna—despite his name having been somewhat synonymous with the city after his grandfather, Sigmund Freud lived and worked there for many years. The show featured many of his most famous works, on loan from major museums across the world, and was put together with assistance from Freud himself (he passed away as the show was being finalised).

This London show is very personal. Freud’s most expert audience is in London, so we felt that we had to get this show right. Because of the nature of the show, it took a lot more detective work—the show became a case of excavation, we really delved into every scribble and sketchbook we could find to discover any representation of his likeness. Whether it was a full-on recognisable painting, such as Painter Working, Reflection (1993), or a sketch reflecting himself in a window, we wanted to include it in this show.

KA: Freud’s work is often compared with Expressionists such as his former friend and contemporary, Francis Bacon. How do you think it is similar and different?

JS: I think Lucian was often in dialogue with Bacon, and while there are many similarities, the differences are pronounced. Someone once said to me, ‘Bacon dissects his subject with a chainsaw—and Freud, with a scalpel.’ I find this to be quite true. Bacon was much more impulsive and given to the ‘accident’ of his work. His mood often dictated his paintings. Lucian, on the other hand, was much more precise.

KA: Freud was notoriously private—does that make this show contradictory to his inherent nature?

JS: Lucian and I spoke about this idea in the latter part of his life, and he was supportive of the idea; however, he wouldn’t have necessarily expected all of these works to be shown together as they are. Ultimately, he painted self-portraits and left a studio—he made a conscious decision to release them. Conversely, though, he asked that his biography be published after his death, and he wanted this show to be posthumous as well. He would’ve been fascinated by seeing it, perhaps not pleasantly, but fascinated nonetheless.

Each time he painted himself, he painted a different person. You don’t paint 80-90 pictures of yourself with the intention of no one ever seeing them. He used them as a discovery into himself—it is why he used mirrors. As he gets older, or fitter, or stronger, whatever it may be, his painting style changes. You feel as if you’re meeting a cast of characters: which is what he intended.

KA: How are his feelings about himself reflected in his work? His feelings about life?

JS: He said that every painting he ever made is a form of a self-portrait. There is only ever one degree of separation between Lucian and his paintings—even a plant is a plant that he feeds and waters, and that accompanies him. His favourite books and pillows, his children, his lovers—they are all inevitably some part of him, and you’re able to see that within each work. The self-portraits are the most direct manifestation of that sentiment.

KA: What do you think Freud’s relevance and importance are concerning art history as a whole?

JS: At the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, the collections go back 5,000 years. The art that we show is akin to the cream that has risen to the top of settled milk, which has taken hundreds of years to agree upon its mastery. When Lucian had his show there, he felt utterly at home in a gallery next to Titian and the Old Masters. He often set up dialogues with the history of art within his own work—and the result is some of his paintings feel like old classics.

I’ve always felt his paintings fall somewhere between historical and contemporary museums, as he drew upon so many traditions from art history, but ultimately had his own indistinguishable and ever-adapting style. I have no doubt that 200 years from now, he will be celebrated and acknowledged in every art history text published.

Interested in art? Discover more about the Quintessentially Art Patrons membership and our fine art advisory and consultancy service.