Even though it has yet to reach its peak, the sun in San Nicola is scorching – the kind of heat that merits jumping from shadow to shadow like puddles. Despite this, a throng of people is jostling in an unshaded section of the street, seemingly immune to the tarmac-melting rays that smell like burnt rubber and, strangely, olive bread. As we edge closer, the source is revealed: a bakery manned by a flour-dusted baker who periodically parts the crowd with trays of pastries and an exasperated 'scuza'.

Sicilians, as it turns out, really love their food. The Mediterranean island has seduced travellers since the time of myths, luring in adventurers with whispers of a land rich in almonds, lemons and pomegranates. Its cuisine isn't Italian per se; it is far-reaching and exotic, with culinary pride so profoundly intertwined with the Sicilian identity that even the mobsters in The Godfather turn to it for comfort.

In truth, I'd arrived in Sicily with preconceived ideas about its food. Like many, I'd sampled arancini (rice balls) and cannoli (ricotta-stuffed pastries) but had little understanding of how each dish is so imbued with history – nor how much of the trip would be taken up by eating. Case in point: we leave the bakery armed with olive-stuffed bread, pockets full of pastries, and clutching muscular loaves still warm from the oven. We only went in for an espresso.

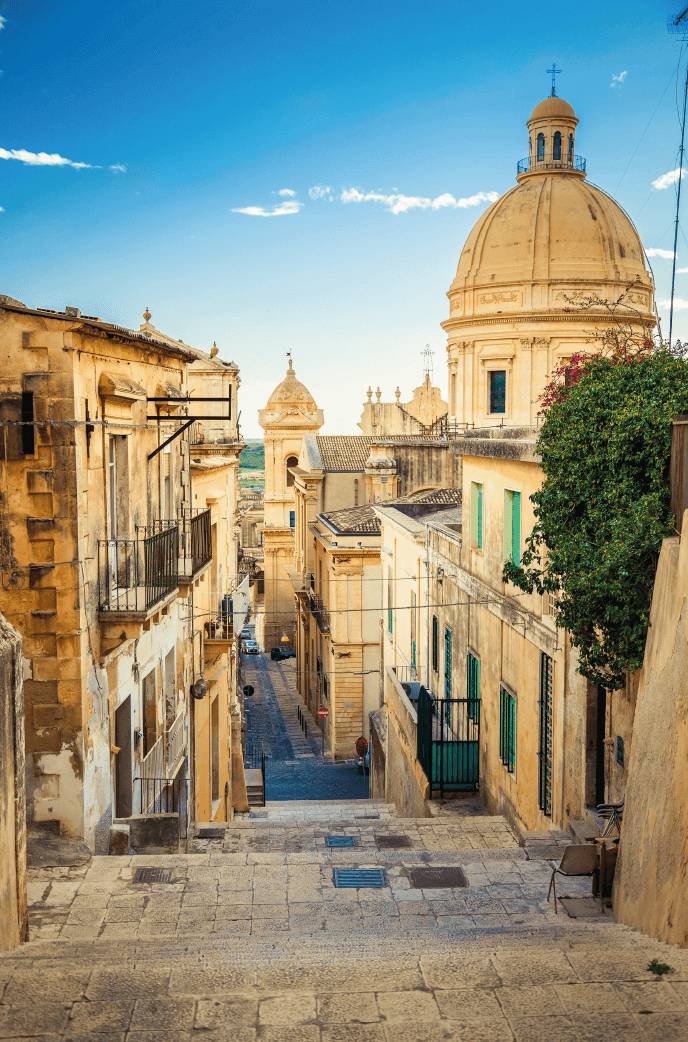

Exploring Sicily's streets

'Sicilian food tells our history.' I'm speaking with Emilia Strazzanti, a Sicilian chef and co-founder of Strazzanti, a family-run company that delivers authentic Sicilian food and wine experiences. 'Eating is a huge part of our day; it's not just going to the supermarket as a convenience. It's about slow living and taking the time to understand what's inside each product.'

The Sicilian store cupboard is certainly worth examining. Its flavours form a layer cake of cuisines and cultures, mapping out its history in edible form. Sugar, rice and pistachios were brought over by Arab settlers; the Greeks brought grains; the Spanish, tomatoes and chocolate; North Africans left behind couscous and saffron. Even its signature Sicilian lemons are an import, carted over by Saracen troops in the 9th century.

As such, a culinary exploration of Sicily feels in order, and we begin in its capital, Palermo. Once the centre of the western world, it's a pockmarked palimpsest of a place, with thousands of years of history etched, cracked and painted over every surface. Forget sitting down for a silver service: Palermitani have been eating food on the move for centuries, and as such, street food is the name of the game here.

Palermo Cathedral

We soon discover how easy it is to end up at a food market, pushed along by the sweltering heat, until we arrive under the umbrellas of Mercato del Capo. We duck under swinging carcasses and peruse globular cheeses and sun-swollen veg whilst wafts of saffron rise from seemingly every stall. Men in flat caps bite into fist-sized arancini at a central wooden bar, pressing breadcrumbs from their mouths with paper napkins.

A few cobbled corners later, we suddenly see the cathedral. It is a patchwork marvel: Byzantine carvings curl over Catalonian gothic gargoyles, Norman towers jostle with Baroque cupolas, and geometric tattoos are etched next to a passage from the Quran. It's a striking emblem of Sicily's crisscross of cultures and a champagne-coloured monument to a heritage constantly on the move.

Come nightfall, we find ourselves in yet another street market: La Vuccira, or 'hubbub'. It lives up to its name: African drumbeats battle with the sizzle of deep fat fryers, bucket-hatted fishermen bellow orders and hurl fistfuls of prawns onto fire-blackened grills. Here, we try panelle (chickpea pancakes) and potato-filled dumplings, which are baptised in oil and reborn as glistening fritters. 'It's a big party here every night of the week,' a barman yells as we watch people flock under a chalkboard advertising spleen sandwiches (a delicacy we forgo in favour of a spritz).

It's almost a relief to journey to sleepy Scopello – a tiny, whitewashed town wrapped around a central baglio. Here, Bombay-blue waves sparkle onto pearly shores whilst the Zingaro Nature Reserve tumbles down the mountainside. Up close, the water is so clear that you can see tiny jellyfish propelling through shoals of fish and underwater fronds. As such, seafood is the order of the day, whether pasta is speckled with sardines, lobster-filled ravioli, or slabs of swordfish stuffed with breadcrumbs and sultanas rolled into involtini.

Involtini de pesce spada in Scopello

This, too, is a history lesson on a plate. Sultanas are sourced from North Africa, bay leaves are gathered from the hillside, and the fish itself is scooped straight out of the sparkling waves. But perhaps most intriguingly, this luxurious dish was born out of poverty. 'We had a lot of noble, wealthy families in Sicily who could afford private chefs and create high-quality dishes,' says Emilia. 'But everyone else would have to find a way to feed a lot of people with little food and ingredients – so they would use the same recipes but swap in breadcrumbs or use water instead of eggs. It was a way of making the food go further.'

Arancini to alla norma, involtini to cannoli… The island's history is so present in every bite that it's a wonder I never recognised it to begin with. In fact, once you start looking for it, you see that food and dining rituals are everywhere. Grocers speak rapidly about their products, even if you speak no Italian. Our driver suddenly swerves to pluck wild fennel from the edge of an olive grove. Crowds of friends prop up bars with espresso or Aperol, or jostle around a lemon-coloured bakery to collect their daily bread.

Casatelle Siciliano

On our final day, we end where we began: in a bakery. We follow our noses to a sleepy spot on the hillside and find casatelle siciliano, conch-shaped pastries stuffed with sweetened ricotta. We pay 2 EUR for two and two espressos and watch as they are slid into paper bags straight from the oven-bent silver trays. They're eaten looking over the sea, and the powdered sugar mingles with the salty air.

Hours later, in the airport, I watch a Sicilian family reunite in the arrivals hall. The grandfather suddenly pulls out a tray of casatelle, and the group erupts into joy and clouds of powdered sugar: sometimes a taste of home is all you need.

For more information or to book a holiday, please contact Quintessentially Travel.